Why Most Corporate Training Sucks

And how to make yours suck less

Good morning, and welcome to Acme Widgets Sales Training. I’m Becca, your trainer; over the next 8 hours, you will learn all about Acme Widgets and how to sell them.

[Slide 1 (of 147): About me] First of all, let me tell you a bit about myself. I joined Acme 5 years ago as a customer service representative…

[Slide 2: Agenda] Here’s today’s agenda: First, “What are widgets?” We’ll spend some time on the history of widgets. Next, we’ll talk about the story of Acme and how we got into the widgets business…

Raise your hand if you’ve been there: several hours of “training”, consisting largely of the instructor reading his or her slides to you (or an e-learning course in which the narrator reads the text on the screen), followed by a quiz to make sure you got it. The course objectives promise that after attending the training, you will “know” or “understand” or “be able to explain” something.

Why is so much corporate training so bad? And if you are responsible for developing or delivering such training, how can you improve the lives of your victims (and, let’s be honest, your own life: nobody enjoys delivering ineffective, mind-numbing training)?

The History of Training

Haha, jk. Seriously, how did corporate training get so bad? I can think of three reasons:

-

We (trainers and instructional designers) are afraid to push back against bad ideas from stakeholders. All too often, someone decides training is the solution to a performance problem; they request a course, and we dutifully create one. That’s our job, isn’t it?

"Doc, give me antibiotics!" Doc: "Okay!" Is this a good doctor? Of course not. "L&D, give me a course!" "Okay!" Good L&D? Nope.

— Cathy Moore (@CatMoore) December 21, 2016Even when training is a valid approach, stakeholders and subject-matter experts frequently demand that we include far too much content. They want us to teach students everything they know (never mind that it took them years to attain their expertise). If we object that there’s not enough time to effectively cover so much content, stakeholders reply that “at least the students will be exposed to the material”, as if they can somehow learn by osmosis.

You can’t teach people everything they need to know. The best you can do is position them where they can find what they need to know when they need to know it. — Seymour Papert

To be truly valuable to our organizations, we must be more than simply course designers or instructors; we must become performance consultants. Don’t create a course just because someone requests one; don’t allow stakeholders to dictate content or instructional approach. Instead, ask why stakeholders think they need a course; what do they want the training to accomplish? If you agree that training is warranted, you recommend the best ways to achieve the stakeholders’ objectives.

Of course, you may not feel confident standing up to stakeholders due to…

-

Lack of formal training. How many of you have received formal education as a trainer or an instructional designer? Yeah, me either. Many of us fell into this role because we were subject-matter experts in some other field. (I was a software developer with social skills.) Some training manager saw our potential and asked, “Hey, do you want to be a trainer?”

If you do get formal training, many degree programs cover instructional-design models from 40 or 50 years ago (I’m looking at you, ADDIE and Bloom) without teaching you how to adapt them to today’s learners and rapidly-changing subject matter.

-

This is all we know. We know our training could be better, but “tell-then-test” is how it’s always been done. (It kills me that university instructors are called “lecturers”.) What else is there?

Here are three ways to create training that learners and stakeholders love, and that effects real change within your organization:

Start with a goal

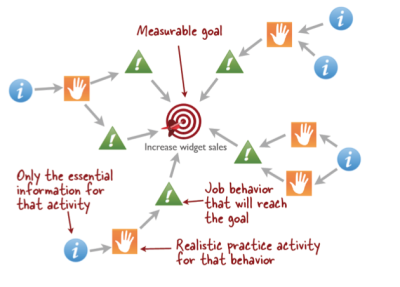

If you’re going to spend time developing a course (and ask people to spend time taking it), the training should have a specific, measurable goal. I like Cathy Moore’s Action Mapping process:

Start with a measurable business goal, then figure out what learners need to do in order to reach it. Identify the minimum information learners need in order to perform the desired behavior and include only that information in the course. If you must provide additional reference material, link to it as an external resource; don’t force-feed it to learners as part of the course.

Perfection is attained, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. — Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Lean, focused training saves your time during development, and ensures that you don’t waste learners’ time: Every moment they spend with your training moves them closer to your goal.

Here’s another great post on this subject that I wish I had written. If you don’t already read Ethan Edwards’ blog, you should start now.

Make it emotional

Quick: Think of your favorite scene from a movie or TV show. Why do you remember that scene? I’ll bet it provoked an emotional reaction – excitement, surprise, laughter, romance – the first time you saw it. People remember (and are moved to action by) experiences that engage their emotions. How can you apply this principle in your training?

A great way to get people emotionally involved is to tell a story, a realistic scenario that helps learners see how the training relates to them.

For example, I began a course on service-oriented architecture (SOA) with a story about Linda, a software developer, and Bill, her manager. Linda wants to use SOA on her current project; she believes the long-term benefits are worth a bit of up-front investment. Bill thinks it’s a nice idea, but there’s not enough time in the schedule to try something new.

The conflict between Linda and Bill invites learners to choose a side and helps get them emotionally involved. Try to think of a story with a plot and characters to which your learners can relate.

For more excellent ideas on creating a memorable message, read Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath.

Make it practical

If your goal is to teach people how to do something, your course should include interactions that allow them to practice the desired behavior. By “interactions”, I don’t mean a multiple-choice quiz or matching terms with their definitions. Learners must be able to practice what you expect them to do on the job, including the ability to make mistakes and see the consequences of those mistakes. Dr. Michael W. Allen recommends a model that he calls CCAF: Context, Challenge, Activity, Feedback.

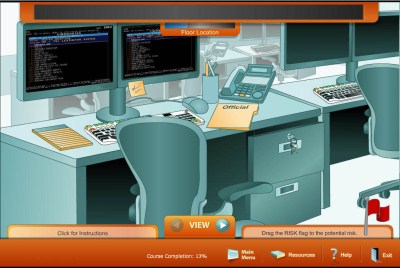

Context is the setting in which the learning takes place. It includes the story you choose to set the scene as well as the visual design of the course, which should be immersive and reflect the learner’s day-to-day work environment as closely as possible.

Challenge refers to creating a desire in the learner to complete the course successfully, a sense that something personal is at stake. Ethan Edwards explains:

When the learner makes forward progress equally, whether an answer is correct or incorrect, he or she learns that it does not really matter what one gives as an answer… If there is no real chance for the learner to fail, then failure or success is a matter of indifference. And if the performance required of the learner seems pointless or irrelevant, there will be little motivation to work toward that end.

The learner must know that success is possible, but that it’s not necessarily guaranteed without some mental effort.

Activity is the physical action the learner must perform to achieve success. Ideally, the activity should mirror as closely as possible what the learner will actually do on the job. The goal is to demonstrate mastery of a skill, not simply the recall of information.

Feedback is the information we communicate to the learner in response to his or her actions. Telling the learner whether he or she completed an activity correctly is just scratching the surface. Instead, you can show the learner the consequences of his or her actions (intrinsic feedback). Or you can give the learner a challenge at the beginning of a lesson, then use feedback after an activity to present the associated content. By tailoring the content to the learner’s needs (as demonstrated through the activity), the instruction takes less time and becomes more relevant, and the learner will be more receptive to it.

For more information on the CCAF model, download this free e-book from Allen Interactions.

Be the change you wish to find in your couch cushions

By starting with a specific, measurable goal, engaging the learner’s emotions, and making the training practical and relevant to the learner, you will greatly increase the appeal and effectiveness of your training.

Have you experienced a memorable training experience (good or bad)? Do you have questions about how to apply this article? Please leave a comment below.

Leave a comment